Category: Tips and Tricks

Articles about tips and tricks for caregivers and nurses caring for the terminally ill.

Articles about tips and tricks for caregivers and nurses caring for the terminally ill.

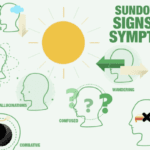

Sundowning, or "late-day confusion," is a challenging experience for individuals with dementia and their caregivers. This phenomenon, occurring in the late afternoon or evening, brings about increased confusion, anxiety, and agitation. Caregivers need to comprehend sundowning and offer compassionate care to ensure the well-being of their loved ones. This article delves into effective pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies to manage sundowning and create a safe environment.

Navigating the challenges of caring for an elderly parent with dementia can be tough, especially when they resist help. This guide offers practical advice and compassionate strategies to support your loved one while respecting their autonomy and dignity.

Discover the potential side effects of dementia medications and how to support your loved one.

Maintaining routines and consistency can significantly improve the overall well-being and quality of life of a loved one with dementia. As a caregiver, understanding the value of routines and how they can positively impact your loved one's journey through dementia is crucial. In this article, we'll explore why routines matter, how to establish them, and their benefits to patients and caregivers.

Discover gentle methods to encourage dementia patients to bathe. Learn how to create a positive bathing experience, use distraction techniques, and maintain a consistent routine. These compassionate approaches help caregivers navigate hygiene challenges while preserving dignity and reducing stress for both patient and caregiver.

Welcome to our discussion on a topic close to many hearts: the care of our loved ones with dementia. When a family member is diagnosed with dementia, it feels like a part of them slowly fades away. But as they lose parts of themselves, your role in their life becomes even more crucial. This article isn’t just words on a page; it’s a beacon of hope and understanding, shining a light on why your voice, as a family member, is vital in the care of your loved one.

When caring for a loved one with dementia, it's important to approach their needs with empathy and understanding. Dementia is a progressive condition that affects memory, thinking, and communication. As a caregiver or family member, it's crucial to adapt your communication style and strategies to best support your loved one. This article will guide you through the stages of dementia, address common symptoms like anxiety and agitation, provide techniques to reduce caregiver burnout, create a calm environment, and effectively respond to repetitive questions.

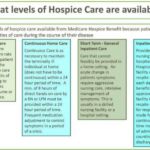

Caring for a loved one who has a terminal illness can be extremely rewarding but also particularly challenging. You may feel exhausted, overwhelmed, or isolated by the demands of caregiving. You may also feel guilty or anxious about taking a break from your loved one. But you deserve time to rest, recharge, and care for yourself. That is why hospice respite care can be a great option for you and your loved one.

Hospice respite care is a service that allows you to temporarily place your loved one in a facility, such as a hospital, nursing home, or hospice house, where they can receive professional care and support. You can use this time to do whatever you need or want, such as sleeping, working, running errands, visiting friends, or enjoying a hobby. Respite care can last up to five days at a time.

Discover compassionate approaches to nourishing terminally ill loved ones. Learn about appetite changes, feeding techniques, and the importance of emotional support during meals. This guide offers practical tips for caregivers to ensure comfort and dignity while addressing nutritional needs in end-of-life care.

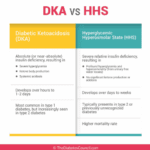

As an experienced hospice nurse, I understand that managing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) at end of life can be challenging, especially when patients choose to stop taking their diabetic medications or when those medications are no longer an option. In this article, I will provide information on recognizing the signs and symptoms of hyperglycemic crises and outline comfort-based treatment options that align with hospice goals of care.

Discover how hospice patients can safely travel and create lasting memories with loved ones. Learn about essential preparations, medical considerations, and tips for a smooth journey. Explore ways to make the most of precious moments together while ensuring comfort and care during travel.

Caring for a loved one with dementia can be challenging. One common struggle caregivers face is ensuring their loved one takes their medications. Dementia can make understanding and remembering medications difficult. In this guide, we'll explore effective strategies for encouraging your loved ones with dementia to take their medications, considering their unique needs.

Facing the reality of a loved one's terminal illness can be a challenging and emotional journey. As a hospice registered nurse case manager, I understand the importance of providing compassionate and clear information to empower patients, caregivers, and families. In this article, we'll explore how you, as a family member, can use your own observations and senses to recognize the signs that your loved one may be in the terminal stage of their illness. Remember, while medical professionals have their tools, your observations and intuition significantly matter.

I know that the journey you and your loved one are on can be challenging, especially when facing a terminal illness. As an experienced hospice nurse caring for terminally ill patients, I want to provide you with some valuable insights on a common issue that may arise during this time: contractures.

In this article, we will discuss how to use the Beers Criteria to identify PIMs and potential prescribing omissions (PPOs) in hospice patients. PPOs are medications that are indicated but not prescribed for a specific patient or population, or that are prescribed at a suboptimal dose or duration. We will also present 10 case studies to illustrate the medication reconciliation and deprescribing process and the outcomes of medication changes in different scenarios.

Caring for someone with dementia requires understanding and a heart full of compassion. This guide highlights the importance of patience and empathy and their profound impact on enhancing the lives of those with dementia.

Discover effective non-pharmacological methods to manage shortness of breath in hospice care. Learn about positioning techniques, breathing exercises, and environmental adjustments that can comfort and relieve patients experiencing dyspnea, enhancing their quality of life during end-of-life care.

Elopement is when a person with dementia leaves a safe area, like their home or care facility, without supervision. This can be intentional or unintentional, and it's important to address to ensure the safety of the patient. If your loved one is attempting to escape from a memory care facility, there are steps you can take to support both them and the facility.

This article will try to help you cope with this challenge. We will give you some information and advice on how to:

Prepare for the transition to a nursing home

Support your loved one during and after the move

Take care of yourself and your family.

Caring for a comatose loved one during their hospice journey requires special attention, particularly when it comes to oral care. In this guide, we'll explore best practices for oral care, considering the unique needs of comatose patients, and provide you with valuable resources for further guidance.

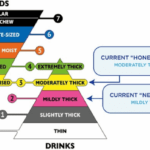

Caring for a loved one with dysphagia during their end-of-life journey can be challenging, but with the proper knowledge and support, you can provide them with comfort and dignity. Dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, is a common symptom in terminally ill patients and can lead to complications if not managed properly. In this guide, we will provide you with essential information on managing dietary changes and what to expect and offer helpful tips and tricks to ensure your loved one's comfort.

Doll therapy offers a compassionate approach to enhancing the quality of life for dementia patients. By providing comfort, reducing anxiety, and promoting social interaction, this non-pharmacological intervention can significantly improve emotional well-being and cognitive function in individuals with dementia.

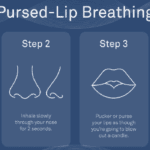

Dealing with shortness of breath can be challenging for terminally ill patients, but there are techniques that can help manage this symptom and improve their overall comfort. One such technique is pursed lip breathing. Pursed lip breathing is a simple and effective breathing technique that can help reduce shortness of breath and improve oxygen exchange in the lungs. As an experienced hospice nurse with years of experience, I will guide you through the steps of pursed lip breathing in a compassionate and easy-to-understand manner.

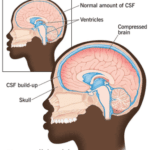

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) is a condition that occurs when cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) builds up inside the skull and presses on the brain. This can lead to various impairments in brain functions, such as thinking, memory, movement, and bladder control. NPH can also affect the quality of life, mood, and behavior of the person with NPH and their caregivers. The cause of NPH is often unknown, but it may be due to injury, bleeding, infection, brain tumor, or surgery on the brain. This article aims to provide a guide for families to understand NPH, its symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and management, as well as how to cope with the challenges and uncertainties of living with NPH.