Category: Terminal Illness

Articles about terminal illnesses that one typically sees and cares for on hospice.

Articles about terminal illnesses that one typically sees and cares for on hospice.

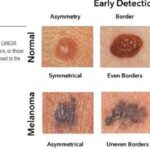

This article is written for families and caregivers of people with melanoma skin cancer. It will explain what melanoma is, how it is diagnosed and staged, what the treatment options are, and how to cope with the physical, emotional, and spiritual challenges of the disease. It will also provide some practical tips and resources to help you and your loved one through this journey.

Doll therapy offers a compassionate approach to enhancing the quality of life for dementia patients. By providing comfort, reducing anxiety, and promoting social interaction, this non-pharmacological intervention can significantly improve emotional well-being and cognitive function in individuals with dementia.

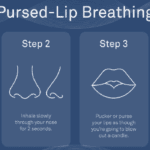

Dealing with shortness of breath can be challenging for terminally ill patients, but there are techniques that can help manage this symptom and improve their overall comfort. One such technique is pursed lip breathing. Pursed lip breathing is a simple and effective breathing technique that can help reduce shortness of breath and improve oxygen exchange in the lungs. As an experienced hospice nurse with years of experience, I will guide you through the steps of pursed lip breathing in a compassionate and easy-to-understand manner.

This comprehensive guide offers a compassionate overview of Huntington's disease, a rare condition that affects the brain. Learn what to expect throughout the course, how to support your loved one's needs, manage your well-being as a caregiver, plan for the future, and access hospice care. Gain insights into providing compassionate care that maximizes quality of life.

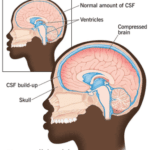

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) is a condition that occurs when cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) builds up inside the skull and presses on the brain. This can lead to various impairments in brain functions, such as thinking, memory, movement, and bladder control. NPH can also affect the quality of life, mood, and behavior of the person with NPH and their caregivers. The cause of NPH is often unknown, but it may be due to injury, bleeding, infection, brain tumor, or surgery on the brain. This article aims to provide a guide for families to understand NPH, its symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and management, as well as how to cope with the challenges and uncertainties of living with NPH.

Caregivers of dementia patients in the final stage face a challenging dilemma: whether to wake their loved ones or let them sleep. This article explores the pros and cons of each approach, offering guidance on making this difficult decision while prioritizing comfort and dignity in end-of-life care.

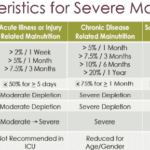

Explore our guide on protein-calorie malnutrition (PCM), a condition hindering proper health for the terminally ill. Learn to recognize symptoms, provide care, and understand the end-of-life journey with our compassionate, informative support for families.

Navigating hospice eligibility for non-Alzheimer's dementia patients demands a personalized approach. Unlike Alzheimer's, there's no definitive scale, necessitating assessments of functional decline, mobility, communication, incontinence, weight loss, overall condition, and comorbidities. Effective documentation, clinical judgment, and compassionate care are crucial for supporting these patients and families.

Caring for a loved one with dementia can be both rewarding and challenging. If your loved one has been restless throughout their life, this restlessness may continue as a symptom of their dementia. As an experienced hospice nurse, I understand the difficulties you may face in managing habitual restlessness while ensuring the safety and welfare of your loved one. In this article, I'll provide you with practical tips and evidence-based practices to create a calming environment for your loved one, even if they have trouble with fine motor control due to arthritis or other factors.

Breast cancer is a tough road, affecting patients and their families deeply. As a hospice nurse case manager specializing in compassionate end-of-life care, I comprehend the significance of offering clear, empathetic guidance to families in this challenging situation. This article delves into the journey through breast cancer, the changes your loved one might undergo, and how to deliver optimal care from diagnosis to life's end.

This article will delve into common infections in geriatric patients, encompassing early, middle, and late-stage symptoms, preventive measures, and prevalent treatment approaches, particularly for patients facing a terminal illness prognosis of six months or less.

Supporting a loved one through their bone cancer journey can be challenging, but with the right knowledge and compassionate care, you can provide meaningful support every step of the way. This guide aims to help you understand what to expect and how to offer the best care possible.

As a hospice registered nurse case manager, I'm here to provide you with information, support, and guidance through this grim time. In this article, we'll explore what to expect over the course of the disease, the changes you might observe in your loved one, and how to provide the best care from the onset of the illness until the end of life.

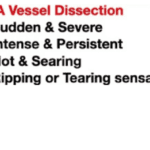

The purpose of this article is to provide you with some information and guidance about AAAs and how they can be managed in hospice patients.

Navigating the tender journey of hospice care, Compassion Crossing offers guidance on addressing the pivotal question of “when?”—a beacon for caregivers seeking solace and understanding in life’s final chapter.

Dealing with a loved one in end stage coma can be an emotionally challenging and overwhelming experience. As an experienced nurse with years of experience, I understand the importance of providing compassionate care and support during this difficult journey. In this article, we will explore what to expect during the course of the disease, changes you might see in your loved one, and essential tips for caring for them from onset until death.

Discover essential information about squamous cell carcinoma, including its causes, symptoms, and treatment options. This comprehensive guide offers valuable insights for families and caregivers, helping you navigate the challenges of supporting a loved one diagnosed with this form of skin cancer.

Explore the complexities of hospice care for terminally ill patients with multiple diagnoses. Learn how to distinguish between related and unrelated conditions, understand Medicare coverage, and navigate the challenges of providing comprehensive care while adhering to hospice regulations and ethical standards.

Dementia gets worse over time, and as caregivers, we want to support our loved ones through every stage. In the severe stages of dementia, a person's body may begin to fail significantly. Here are seven ways to promote their quality of life during this challenging time.

Discover essential guidance for caring for a loved one with Alzheimer's disease, from early symptoms to end-of-life care. Learn about communication strategies, safety measures, and self-care tips for caregivers. This comprehensive guide offers support and practical advice for navigating the challenges of Alzheimer's caregiving.

LATE, a newly recognized form of dementia affects memory and behavior in older adults. Learn about its symptoms, diagnosis, and how it differs from Alzheimer's. Discover practical tips for caregivers to provide compassionate support and improve the quality of life for loved ones with LATE.

Identifying when a patient may benefit from hospice care is a critical yet often challenging task. For caregivers, including Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs) and Medical Technicians (Med Techs), visual observation can be a powerful tool for recognizing signs that suggest a hospice referral might be appropriate.

This guide is tailored to assist caregivers in personal care facilities in identifying these signs through visual observation methods, helping provide compassionate and timely end-of-life care.

Discover the essentials of ALS, from its symptoms and progression to treatment options and support strategies. This comprehensive guide empowers families facing an ALS diagnosis with knowledge and practical advice, helping them navigate the challenges and provide the best care for their loved ones.

If you are caring for a terminally ill patient in hospice, you know how challenging it can be to manage their medications. You want to make sure they are getting the best possible care, but you also want to avoid unnecessary or harmful drugs that may worsen their quality of life or cause adverse effects.

That’s where medication reconciliation and deprescribing come in. Medication reconciliation is the process of reviewing and updating the patient’s medication list to ensure accuracy and completeness. Deprescribing is the process of reducing or stopping medications that are no longer needed, effective, or appropriate for the patient’s condition and goals of care.