My Loved One with Dementia

Published on June 13, 2022

Updated on July 31, 2025

Published on June 13, 2022

Updated on July 31, 2025

Table of Contents

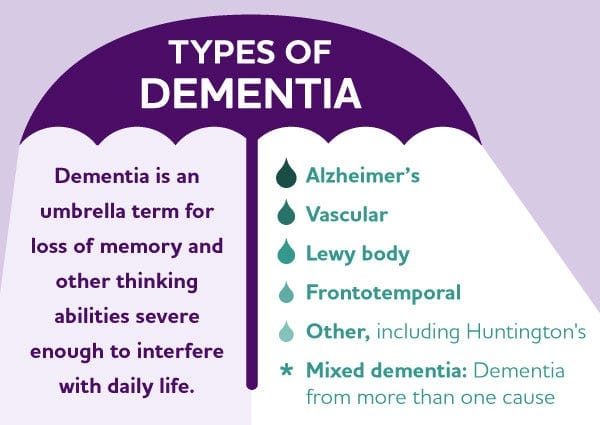

This article helps families and caregivers better understand Dementia. There are many types of Dementia, with the most common being Alzheimer’s, which accounts for approximately 60% of cases. Each type has its particularities, but all involve an increasing inability to make safe choices regarding daily living activities.

Dementia is a term used to describe symptoms that affect a person’s ability to think, remember, and carry out everyday activities. It is not a normal part of aging and is not caused by a single disease. There are many different causes of Dementia, and some forms of it, such as Korsakoff’s Dementia, can be treated. People with Dementia may experience difficulties with memory, communication, reasoning, and emotions. They may also exhibit changes in behavior or hallucinate. Individuals with Dementia require complete care as they regress mentally, emotionally, and functionally, like that of an unborn baby. Coping with Dementia can be challenging, both for the person who has it and for their family and friends. That is why it is crucial to learn more about Dementia and how to support people with it.

There are currently thirteen (13) known types of dementia:

| Type of Dementia | Description | Stages | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | A progressive brain disorder that damages and kills brain cells, causing memory loss and cognitive decline. | Early: FAST 1-3, Middle: FAST 4-5, Late: FAST 6, Terminal: FAST 7 | Trouble remembering recent events, confusion, disorientation, mood and personality changes, difficulty speaking, writing, and swallowing. |

| Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) | A brain disorder that occurs when the brain gets hurt many times, affecting the brain cells that control memory, thinking, and emotions. | Early: Mild cognitive impairment, Middle: CTE, Late: Severe CTE | Problems with memory, thinking, and controlling emotions, personality and behavior changes, anger, sadness, hallucinations. |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) | A rare brain disorder that occurs when a bad protein in the brain called a prion causes the brain cells to die, affecting the brain cells that control memory, thinking, and movement. | Early: Possible CJD, Middle: Probable CJD, Late: Definite CJD | Problems with confusion, vision, speech, and balance, muscle twitches, seizures, and hallucinations. |

| Frontotemporal dementia | A brain disorder that occurs when the front and side parts of the brain are damaged, affecting the brain cells that control personality, behavior, and language. | Early: Behavioral variant or primary progressive aphasia, Middle: Frontotemporal dementia, Late: Severe frontotemporal dementia | Changes in personality and behavior, loss of interest, impulsivity, problems with speaking, understanding, and writing. |

| Huntington’s disease | A genetic brain disorder that occurs when a faulty gene causes the brain cells to die, affecting the brain cells that control movement, thinking, and emotions. | Early: Pre-manifest or prodromal, Middle: Early or middle stage, Late: Late or end stage | Involuntary movements, problems with memory, concentration, and judgment, mood and personality changes, depression, irritability, aggression. |

| Korsakoff dementia | A brain disorder that occurs when a lack of vitamin B1 causes the brain cells to die, affecting the brain cells that control memory and emotions. | Early: Wernicke’s encephalopathy, Middle: Korsakoff syndrome, Late: Chronic Korsakoff syndrome | Severe memory loss, confabulation, problems with coordination and balance, eye movement abnormalities, low blood pressure, fast heart rate. |

| Lewy body dementia | A brain disorder that occurs when abnormal protein deposits called Lewy bodies build up in the brain, affecting the brain cells that control memory, thinking, and movement. | Early: Mild cognitive impairment, Middle: Lewy body dementia, Late: Severe Lewy body dementia | Problems with attention, alertness, visual perception, hallucinations, Parkinson’s symptoms, sleep disorders, fluctuations in cognition and behavior. |

| Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) | A brain disorder that occurs when a protein called TDP-43 builds up in the brain and damages the brain cells that control memory and emotions. | Early: Mild cognitive impairment, Middle: LATE, Late: Severe LATE | Problems with memory, especially recent memory, mood changes, depression, and anxiety. |

| Mixed dementia | A condition where a person has more than one type of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, or Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia. | Depends on the types of dementia involved | Depends on the types of dementia involved |

| Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) | A brain disorder that occurs when a buildup of fluid in the brain puts pressure on the brain, affecting the brain cells that control walking, thinking, and bladder control. | Early: Possible NPH, Middle: Probable NPH, Late: Severe NPH | Problems with walking, memory, concentration, and reasoning, urinary incontinence, apathy, mild dementia. |

| Parkinson’s dementia | A brain disorder that occurs when the brain cells that produce dopamine die, affecting the brain cells that control movement, memory, and thinking. | Early: Parkinson’s disease, Middle: Parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment, Late: Parkinson’s disease dementia | Problems with memory, attention, and planning, hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia, Parkinson’s symptoms, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders. |

| Vascular dementia | A brain disorder that occurs when the blood vessels in the brain are damaged or blocked, reducing the blood flow to the brain and causing brain cell death. | Early: Mild cognitive impairment, Middle: Vascular dementia, Late: Severe vascular dementia | Problems with thinking, planning, organizing, speaking, walking, and controlling emotions. |

| Logopenic Primary Progressive Aphasia | Logopenic Primary Progressive Aphasia, often abbreviated as LPPA, is a rare type of dementia that primarily affects language skills. Imagine a library where the books are in perfect condition, but the librarian struggles to find the right ones. That’s what LPPA is like. The person’s knowledge is intact, but finding the right words becomes increasingly tricky. | Stage 1, Very Mild; Stage 2, Mild; Stage 3, Moderate | The symptoms of LPPA primarily involve difficulties with language. It’s as if the words are hidden in a dense fog, and the person struggles to find them. |

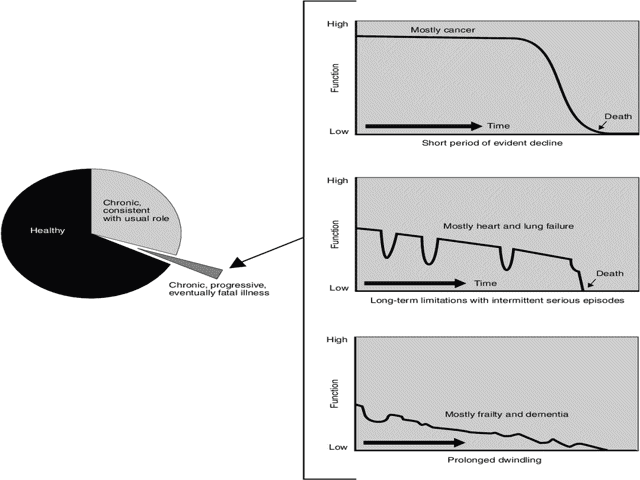

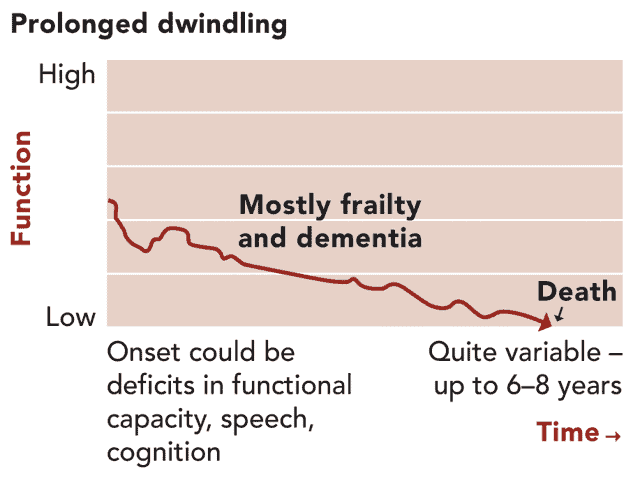

All progressive illnesses have a trajectory for how the loved one declines over time. Those with cancer tend to be highly functional until towards the end, when they have a downward, predictable slope. Those with heart and lung failure have a series of exacerbations along a steady decline before death.

Dementia tends to be like an odd roller coaster that keeps going downhill with slight ups here and there as your loved one has less and less ability to function, yet lingers.

Families have shared that their loved one’s Dementia started anywhere from ten to fifteen years ago. Just now, they are coming onto hospice services. Often, after six months had passed, they thought their loved one would be gone by now. Dementia is one of those progressive illnesses where one can be in the “terminal phase” of the illness (for Dementia, FAST 7A and beyond — see the FAST scale below) for months to years.

Dementia can be thought of as a journey that progresses in stages, and each person’s experience is unique. It’s categorized into three phases: early, middle, and late (Alzheimer’s Disease is the only type of Dementia that has seven stages, with stages six and seven having substages).

Understanding these stages helps you, as a caregiver, prepare for the changes ahead and provide appropriate care.

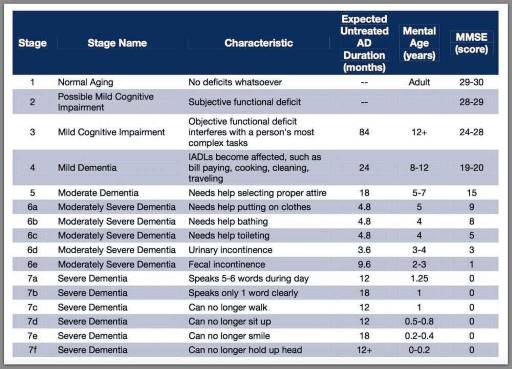

The FAST Scale—Functional Assessment Staging Tool—created by Dr. Barry Reisberg, was designed to assess the stage of Dementia in a person with Alzheimer’s disease.

While the FAST scale is specifically for Alzheimer’s (it’s the only Dementia that follows the FAST scale to the letter in linear order — one stage before the other, including the substates of 6 and 7) — it is also used for other dementias to provide a ballpark of where someone may be at. For Alzheimer’s, always use the current stage the patient is at; for other Dementia patients, I was taught to use the worst stage they are at if that stage is steady (not hit and miss).

The main caveat for all Dementia comes to the inability to walk; if neurological (due to Dementia), it’s the stage (7C on up); if it is skeletomuscular (car accident, falls unrelated to Dementia, etc.), then evaluate the person based on the highest level of function. Stages 1–3 are considered early, stages 4–5 are middle, stage 6 is late, and stage 7 is the terminal stage. A person can be in any stage (or substage) for any period without too much warning about when they will move to the next stage.

None of the stages or substages tells you how long the person has to live. I still remember my FAST 7F Alzheimer’s patient who was on hospice for close to two years (stick and bones also suffering from cachexia) and was able to remain on hospice that long (terminal prognosis for hospice is around six months or less) due to frequent declines through each benefit period before dying.

As you navigate the journey of caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease, understanding the stages of Dementia can provide valuable insights into their condition and needs. The Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST Scale) is a helpful resource designed to assess the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and guide caregivers in providing appropriate support.

By familiarizing yourself with the FAST Scale and applying it thoughtfully to your loved one’s care, you can enhance your ability to provide personalized support tailored to their evolving needs.

You start in stage 1 and review what functionality is lost (it’s not about memory per se regarding Alzheimer’s stages). You then review state 1 functions—yes or no, for what they can and cannot do, and they are just below the “can do.”

Then stage 2, then stage 3… the moment you reach a stage where the person has a function, you are the stage before it.

For example:

Stage 6C – Does not know how to use a toilet BUT knows when they must urinate or have a bowel movement (i.e., they are continent of urine and bowel).

Stage 6D – Incontinent of bladder (includes accidents as well as those they would have accidents if you did not make them go to the toilet)

Stage 6E – Incontinent of the bowel (same deal with accidents, et).

Let’s say you are going through the list, and they meet Stage 6C but are continent of bowel and bladder. Then, your loved one is at Stage 6C.

If you read the list and see 7C, they cannot walk. Your loved one is entirely continent of bowel and bladder but cannot walk; they are still 6C, and it’s another issue than the disease as to why they cannot walk.

A person with Dementia can often present with either hyperactivity (anxiety, agitation, combative behaviors) or hypoactivity (naps, sits, sleeps, minimal activity). For the former, always review medications (see medication considerations below), as two commonly prescribed medications for Dementia are not permanently discontinued when the patient is in the latter (stage 6) to terminal (stage 7) of Dementia, which can cause agitation and combative behaviors.

For those with anxiety and agitation, consider discussing medical cannabis, CBD oil, and Ashwagandha, as well as having the provider assess for pain, as undiagnosed pain can lead to increasing anxiety and agitation as well as paranoia. For those dealing with hypoactivity, consider discussing antidepressant medications as well as undiagnosed pain.

Both presentations involve uncontrollable memory loss at both the conscious and subconscious levels. The inability to remember can affect the ability to make sound judgments and lead to poor impulse control.

Medications commonly utilized to try to slow down the cognitive decline in patients with dementia can cause severe side effects for the loved ones with dementia when they are on them too long. They can work wonderfully if prescribed in stages 1 through 3, and in rare cases, in the later stages (4 and 5). However, starting in stage 6 can create problems for the patient and their family.

Dementia patients are incapable of connecting the dots; they are not able to comprehend why they cannot do something that looks easy or otherwise should be doable by them, or cannot be done by anyone. They cannot understand the risks involved. Those two medications, in stages 6 and 7, may allow the patient to continue to appear more cognitively. Still, when they try to act on what they think they can do and fail, they become frustrated, agitated, and anxious.

All patients with dementia have poor impulse control and a lack of safety awareness and judgment; those medications can result in increased falls and risk for severe injury from those falls as they continue to try things they believe they can do — yet cannot do safely, if at all.

If your loved one is anywhere in stage 6 or later of dementia, please talk with your loved one’s doctor, asking them to discontinue both medications. You may also want to review the other medications your loved one takes to determine the risks versus benefits, per the BEERS criteria. Please don’t presume that your providers use or are aware of the BEERS criteria.

One of the reasons polypharmacy is shared among the elderly is due to the very fact that most providers do not regularly review the medications their patients are taking to determine if they still need to be taken, are causing more problems than they are worth, and so on.

One last medication to review, and this one controversial for many reasons, is the drug category of statins. Statins may help lower bad cholesterol (LDL) while potentially increasing good cholesterol (HDL). Statins include atorvastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin, but they are not limited to these.

One of the side effects of statins is memory loss and confusion, which your loved one is already having and does not need to move faster.

From the article titled, Cholesterol Drugs for People 75 and Older:

Statins have risks: “Compared to younger adults, older adults are more likely to suffer serious side effects from using statins. Statins can cause muscle-related problems, including aches, pains, or weakness. Rarely, a severe form of muscle breakdown can occur.

In older adults, statins can also cause:

Often, older adults take many drugs. These can interact with statins and lead to severe problems. Side effects, like muscle pain, may increase. Statins can also cause a fatal reaction when taken with heart rhythm drugs.

Statins may increase the risk of type-2 diabetes and cataracts, as well as damage to the liver, kidneys, and nerves.”

At the one hospice agency where I worked, the medical director discontinued all statins for every patient, including those on for heart failure, as statin medications at the end of life have terrible side effects that can severely impact the comfort of those patients.

Naomi Feil is an acknowledged expert on using validation therapy as the best means of communicating with people with Dementia. Validation therapy focuses on encouraging and uplifting communication with your loved one, validating their feelings, and avoiding confrontation and correction.

When it comes to communicating effectively with those who have Dementia, and for me, validation therapy can be used for any communication. Validation therapy is the only way to create win-win scenarios. If you focus on trying to educate, correct their words, and correct their thought processes — i.e., fix them — you will end up in combative situations that can quickly escalate into a nightmare.

If you are caring for a loved one with Dementia, you may have heard of hospice care, but you may not know what it is or when it is appropriate. Hospice care is a particular type of care that focuses on providing comfort and support to people with life-limiting illnesses and their families. It aims not to cure the disease but to ease its symptoms and improve the quality of life during the final stages.

Hospice care can benefit people with Dementia and their families in many ways. It can help manage the pain, agitation, and distress common in advanced Dementia. Hospice care can also provide emotional and spiritual support to the person with Dementia and their loved ones, as well as practical assistance with daily tasks and caregiving. Depending on the patient’s and family’s needs and preferences, hospice care can be provided at home, in a hospice facility, or in a nursing home.

Hospice care is available to people with a life expectancy of six months or less, as determined by a physician. However, this does not mean hospice care will end after six months. Hospice care can continue if the person meets the eligibility criteria and the family wishes to receive it. For people with Dementia, the eligibility criteria may include experiencing multiple physical and mental declines, such as losing weight, having difficulty swallowing, being bedridden, or having severe cognitive impairment. Hospice care may also be appropriate for people with Dementia who require frequent nursing care or who have recurrent infections that are hard to treat or prevent.

Dementia is a progressive disease that affects the brain and causes memory loss, confusion, and behavioral changes. There are distinct types and stages of Dementia, but one of the most common and severe forms is Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease can be measured by the FAST Scale, which stands for Functional Assessment Staging. The FAST Scale has seven stages, from 1 to 7, that describe the functional decline of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Stage 7 is the most advanced, indicating that the person may benefit from hospice care.

Some of the signs and symptoms that are typical of stage 7 on the FAST Scale are:

Another sign that hospice care may be appropriate for someone with Dementia is severe cognitive impairment. This means that the person has no awareness of self, environment, or time and cannot recognize familiar people or objects. The person may not respond to their name, may not know where they are or what day it is, and may not remember their spouse, children, or friends. The person may also hallucinate, have delusions or paranoia, and may become agitated or aggressive.

Other signs and symptoms that indicate hospice care may be appropriate for someone with Dementia are recurrent infections and difficulty swallowing, eating, or drinking. Recurrent infections, such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, or sepsis, are common in people with advanced Dementia, and they can be life-threatening or cause complications. Difficulty swallowing, eating, or drinking can lead to weight loss, dehydration, or malnutrition and can also increase the risk of choking or aspiration. These conditions can affect the person’s comfort and well-being and may require hospice care to manage them.

Pain, agitation, or distress are also signs and symptoms that indicate hospice care may be appropriate for someone with Dementia. Numerous factors, including infections, injuries, pressure ulcers, and arthritis, can cause pain. It can be hard to detect or measure in people with Dementia, who may not be able to express or report it. Agitation or distress can be caused by cognitive impairment, environmental factors, or unmet needs, and it can manifest as restlessness, anxiety, anger, or depression. Pain, agitation, or distress can significantly impact a person’s quality of life and overall comfort. It may require hospice care to relieve them with medication or other interventions.

Hospice care can make a difference for people with dementia and their families in the final stages of the disease. It can help improve a person’s comfort and dignity, reducing their suffering and stress. Hospice care can also help the family cope with the emotional and practical challenges of caring for a loved one with dementia and provide them with guidance and support. Hospice care can help the family prepare for the end of life and the grief process and offer them bereavement services after the death of their loved one.

If you think that hospice care may be suitable for your loved one with dementia, you should talk to your physician and the hospice team about your options and preferences. They can help you determine the eligibility and availability of hospice care and explain the benefits and services that hospice care can provide. They can also help you find and select a hospice provider that meets your needs and expectations.

Numerous resources and contact information are available to help you learn more about hospice care and find a hospice provider in your area. Some of them are:

Hospice care can be a valuable option for your loved one with dementia and your family. Hospice care can help you make the most of the time you have left with your loved one and provide you with comfort and support. Hospice care can help you honor your loved one’s wishes and values and celebrate their life and legacy. Hospice care can help you say goodbye to your loved one with peace and grace.

Dementia is a disease that affects the brain and causes memory loss and confusion. As the disease gets worse, the person with dementia may have trouble making decisions, controlling their impulses, and staying safe. A person with dementia may live for a long time with the disease, and this can be extremely hard for the family. The FAST scale is one way to measure the progression of the disease, but it does not indicate how much longer the person will live. The family should talk to the doctor about the medications and treatments that the person with dementia is taking and see if they can stop some of them that may cause more harm than good. The family should also consider using validation therapy, a communication method that helps individuals with dementia feel understood and respected.

Hospice care is another option that the family can consider for the person with dementia. Hospice care is a type of care that supports individuals who are severely ill and nearing the end of their lives. Hospice care does not try to cure the disease but rather to make the person comfortable and peaceful. Hospice care can also help families cope with their feelings and challenges, providing them with support and guidance. Hospice care can be given at home, in a hospice facility, or in a nursing home, depending on what the person and the family want.

Hospice care is typically provided to individuals who have six months or less to live, as determined by their doctor. However, this does not mean hospice care will stop after six months. Hospice care can continue if the person requires it and the family wishes to continue it.

Some of the signs that show that hospice care may be right for the person with dementia are:

Hospice care can make a significant difference for both the person with dementia and their family. Hospice care can help improve a person’s comfort and dignity, reducing their suffering and stress. Hospice care can also help the family deal with the emotional and practical issues of caring for a loved one with dementia and prepare them for the end of life and the grief process. Hospice care can help the family honor the person’s wishes and values and celebrate their life and legacy. Hospice care can help families say goodbye to their loved ones with peace and dignity.

SEVERE Dementia – 7 Ways to Boost Quality of Life (video)

Stages of Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Durations & Scales Used to Measure Progression (GDS, FAST & CDR)

MCI, Alzheimer’s and Dementia. What’s the Difference? – HOP ML Podcast (video)

How to read and apply the FAST Scale to stage any type of dementia. Dementia Staging Made Easy

📚 This site uses Amazon Associate links, which means I earn a small commission when you purchase books or products through these links—at no extra cost to you. These earnings help me keep this website running and free from advertisements, so I can continue providing helpful articles and resources at no charge.

💝 If you don’t see anything you need today but still want to support this work, you can buy me a cup of coffee or tea. Every bit of support helps me continue writing and sharing resources for families during difficult times. 💙

Geri-Gadgets – Washable, sensory tools that calm, focus, and connect—at any age, in any setting

Dementia Caregiver Essentials: Comprehensive Guide for Dementia Care (one book that contains the ten books below for less than one-third the price of all ten)

Dementia Home Care: How to Prepare Before, During, and After

DEMENTIA DENIED: One Woman’s True Story of Surviving a Terminal Diagnosis & Reclaiming Her Life

Atypical Dementias: Understanding Mid-Life Language, Visual, Behavioral, and Cognitive Changes

Fading Reflection: Understanding the complexities of Dementia

Ahead of Dementia: A Real-World, Upfront, Straightforward, Step-by-Step Guide for Family Caregivers

Four Common Mistakes by Caregivers of Loved Ones with Dementia and What Do Differently (video)

Articles on Advance Directives

CaringInfo – Caregiver support and much more!

The Hospice Care Plan (guide) and The Hospice Care Plan (video series)

Surviving Caregiving with Dignity, Love, and Kindness

Caregivers.com | Simplifying the Search for In-Home Care

Geri-Gadgets – Washable, sensory tools that calm, focus, and connect—at any age, in any setting

Healing Through Grief and Loss: A Christian Journey of Integration and Recovery

📚 This site uses Amazon Associate links, which means I earn a small commission when you purchase books or products through these links—at no extra cost to you. These earnings help me keep this website running and free from advertisements, so I can continue providing helpful articles and resources at no charge.

💝 If you don’t see anything you need today but still want to support this work, you can buy me a cup of coffee or tea. Every bit of support helps me continue writing and sharing resources for families during difficult times. 💙

VSED Support: What Friends and Family Need to Know

Take Back Your Life: A Caregiver’s Guide to Finding Freedom in the Midst of Overwhelm

The Conscious Caregiver: A Mindful Approach to Caring for Your Loved One Without Losing Yourself

Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved

Final Gifts: Understanding the Special Awareness, Needs, and Communications of the Dying

Between Life and Death: A Gospel-Centered Guide to End-of-Life Medical Care

Providing Comfort During the Last Days of Life with Barbara Karnes RN (YouTube Video)

Preparing the patient, family, and caregivers for a “Good Death.”

Velocity of Changes in Condition as an Indicator of Approaching Death (often helpful to answer how soon? or when?)

The Dying Process and the End of Life

Gone from My Sight: The Dying Experience

The Eleventh Hour: A Caring Guideline for the Hours to Minutes Before Death

By Your Side, A Guide for Caring for the Dying at Home

Top 30 FAQs About Hospice: Everything You Need to Know

Understanding Hospice Care: Is it Too Early to Start Hospice?

What’s the process of getting your loved one on hospice service?

Picking a hospice agency to provide hospice services

National Hospice Locator and Medicare Hospice Compare

Bridges to Eternity: The Compassionate Death Doula Path book series:

Additional Books for End-of-Life Doulas

VSED Support: What Friends and Family Need to Know

Find an End-of-Life Doula

At present, no official organization oversees end-of-life doulas (EOLDs). Remember that some EOLDs listed in directories may no longer be practicing, so it’s important to verify their current status.

End-of-Life Doula Schools

The following are end-of-life (aka death doula) schools for those interested in becoming an end-of-life doula:

The International End-of-Life Doula Association (INELDA)

University of Vermont. End-of-Life Doula School

Kacie Gikonyo’s Death Doula School

Laurel Nicholson’s Faith-Based End-of-Life Doula School

National End-of-Life Doula Alliance (NEDA) – not a school, but does offer a path to certification

Remember that there is currently no official accrediting body for end-of-life doula programs. It’s advisable to conduct discovery sessions with any doula school you’re considering—whether or not it’s listed here—to verify that it meets your needs. Also, ask questions and contact references, such as former students, to assess whether the school offered a solid foundation for launching your own death doula practice.