How to Identify End-Stage Parkinson’s for Hospice Admission

Published on June 19, 2024

Updated on July 27, 2024

Published on June 19, 2024

Updated on July 27, 2024

Table of Contents

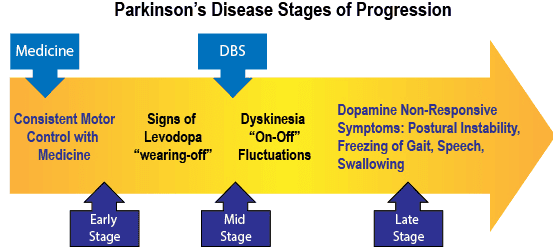

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects the motor system, causing tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. PD also has many non-motor symptoms, such as cognitive impairment, mood disorders, sleep problems, autonomic dysfunction, and pain. PD is a chronic and incurable condition that worsens over time and can lead to significant disability and reduced quality of life.

Hospice care is a specialized form of palliative care that provides comfort and support to patients with terminal illnesses and their families. Hospice care relieves symptoms and enhances the patient’s physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. Hospice care also offers bereavement services to the family after the patient’s death.

However, admitting patients with end-stage PD to hospice care can be challenging for several reasons. First, there is no clear definition of what constitutes end-stage PD, as the disease progression and prognosis vary widely among individuals. Second, there are no specific criteria or guidelines for determining hospice eligibility for PD patients, unlike other terminal conditions such as cancer or heart failure. Third, there may be barriers to hospice referral, such as a lack of awareness, misconceptions, or reluctance among patients, families, or healthcare providers.

This article will discuss the challenges and criteria of admitting patients with end-stage PD to hospice care. We will also share the experiences and insights of hospice professionals who have cared for PD patients and their families.

Over the past six years (at the time of authoring this article), between three separate hospice agencies, there has been a pattern of admitting patients for Parkinson’s’ Disease where the result is frequent discharges for failure to decline. For every four admissions, approximately one patient dies within six to nine months.

For those that were hospice appropriate, I’ve worked with both ends of the spectrum where, on one end, the patient became so stiff they had trouble breathing, was on oxygen, was only oriented to self, and was complete care, including feeding to the other end of the spectrum where they would have spells of looking as if they were on a horse trying to throw them off. When they were not having such severe tremors that medications could no longer manage, they could partially participate in self-care, such as feeding themselves.

Quick Flips doesn’t list specifications for End Stage Parkinsons, and from researching Medicare briefly describes the following:

Yet for the patients I’ve had that fit, the only thing true has been the wheelchair or bedbound status. All the patients that died within the expected time went through normal disease progression vs. rapid (it was rapid in the last three months, but not rapid in the preceding three), did have intelligible speech, and only progressed in diet in the last month.

Therefore, question: Can any of you provide details as to what your admission team (whether one person or many) looks at specifically to ensure that a patient being admitted for End-Stage Parkinson’s is most likely going to die in at least one year after admission? I.e., How can we all be more accurate in admitting Parkinson’s patients when they are in the terminal stage?

Our LCDs do not have a special guideline (CGS) for Parkinson’s. We’ve traditionally looked at them as akin to a patient who meets the general criteria we’d want for general admission. Decline in function, decreased PPS, increased falls, increased unexpected MD visits, ED visits, or hospitalizations in last 6 months, assessment, collab with community provider and talking it through with our admitting doc.

SchoolAcceptable8670

We feel like it has worked well, and live discharge hasn’t been an issue

We often pair PD with weight loss. And I agree that sometimes the pureed diet and speech issues do not happen until the very end.

Gail Bowman

Unintentional weight loss Increased swallowing and/or speech difficulties Aspiration pneumonia Increased significant challenges with mobility Increased episodes of locking joints Increased frequency of UTIs isn’t as common, but when combined with the others we’ll use this as well

1dad1kid

Dysphagia, chair bound, weight loss, frequent falls or at least 3 in past 6 months

Do they ever ambulate or transfer? If so, what does that look like? Short of breath with minimal exertion? x2 moderate assist? x1 max assist? Gait unsteady if ambulatory? How about conversations? Does the patient make sentences? Speech mumbled? SOB noted when verbally communicating?

How is he eating? Full assistance? Choking episodes suggesting progression of dysphasia? Eating x3 meals a day? Meats cut up d/t choking or swallowing difficulties?

Shay Bates

Decline in speech, swallowing, amount of hours slept per day, weight loss, shuffling, inability to walk 50 feet unassisted

Kylie Winn

I admitted a gentleman who was still walking and talking, eating, and with only occasional incontinence. . I asked our MD why he felt he was eligible, he said because he was sleeping 20-22 hours per day. Huh?? And sure enough, he was gone in six months. I’m still scratching my head over that one.

Tina Kraakman

I don’t have any official documentation but in my experience the Parkinson’s patients that are truly appropriate are PPS 30%, with disease progression to the point it’s affected their swallowing and respiratory status (difficulty managing even their saliva). Pureed diet typically. They are at least wheelchair bound as you described. If they’ve declined to the above within the past 3-6 months, had the other supporting factors like weight loss of 10% in the past few months or aspiration pneumonia in my opinion that paints a good picture. Again, the biggest marker of true end stage status (in my experience) has been the disease affecting the mouth/throat and respiratory status.

okreddituwin

Don’t forget falls and confusion. And with some ES Parkinsons there is a HUGE spike in anxiety. Medication changes qualify as decline.

cryptidwhippet

Let’s look at three areas that help us determine if the patient is within six months or less.

To be eligible for hospice care, patients must have a life expectancy of six months or less. This is based on documented evidence of the decline in clinical status. The guidelines below show how to measure this decline over time. Both baseline and follow-up data should be reported when possible. Baseline data can be from hospice admission or previous records. Other clinical factors not on this list may also indicate a short life expectancy. These should be recorded in the clinical file.

The decline in clinical status must be irreversible. The guidelines are ranked by how well they predict survival, from the most accurate to the least accurate. No fixed number of guidelines must be met, but more of the less accurate and fewer of the more accurate ones are expected to show a life expectancy of six months or less.

| Guideline | Description |

|---|---|

| 1) Progression of disease | The disease gets worse as shown by clinical status, symptoms, signs, and laboratory results |

| A) Clinical Status |

|

| B) Symptoms |

|

| C) Signs |

|

| D) Laboratory |

|

| 2) Decline in Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) or Palliative Performance Score (PPS) | Lower scores on scales that measure physical function and quality of life |

| 3) Increasing emergency room visits, hospitalizations, or physician’s visits related to hospice primary diagnosis | More frequent use of health care services due to worsening of disease |

| 4) Progressive decline in Functional Assessment Staging (FAST) for dementia | Higher scores on a scale that measures the stages of dementia (from 7A or higher on the FAST scale) |

| 5) Progression to dependence on assistance with additional activities of daily living | Needing more help with daily tasks such as bathing, dressing, eating, etc. (See Non-Disease Specific Baseline Guidelines, Section 2) |

| 6) Progressive stage 3-4 pressure ulcers despite optimal care | Developing or worsening bed sores that are hard to heal even with the best care |

| Guideline | Description |

|---|---|

| 1) Physiologic impairment of functional status | Low scores on scales that measure physical function and quality of life (Karnofsky Performance Status or Palliative Performance Score <70%) |

| 2) Dependence on assistance for two or more activities of daily living (ADLS) | Needing help with daily tasks such as:

|

Note: The word “should” in the disease-specific guidelines indicates that the guideline will be crucial in deciding whether the patient is eligible for coverage. However, it does not mean the patient must meet the guidelines to qualify.

When deciding if someone is eligible for hospice care, the primary diagnosis is not the only factor to consider. Other diseases that are present and severe enough to shorten the person’s life span to less than six months should also be considered.

| A. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | B. Congestive heart failure | C. Ischemic heart disease |

| D. Diabetes mellitus | E. Neurologic disease (CVA, ALS, MS, Parkinson’s) | F. Renal failure |

| G. Liver Disease | H. Neoplasia | I. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome |

| J. Dementia |

Suggested hospice guidance for Parkinson’s disease and related disorders, one of the following three criteria are required

| 1. Demonstrates evidence of advanced disease as manifested by either A, B, or C criteria | A. Critical nutrition impairment in the prior year (inability to maintain sufficient fluid/caloric intake and dehydration, or BMI<18, or 10% weight loss over six months and refusal of artificial feeding methods); or |

| B. Life-threatening complications in the prior year (recurrent aspiration pneumonia, falls with fractures, pyelonephritis, sepsis, recurrent fever, or stage 3 or 4 pressure ulcers); or | |

| C. Motor symptoms that are poorly responsive to dopaminergic medications or which cannot be treated with dopaminergic medications due to unacceptable side effects and result in significant impairments in the ability to perform self-care or | |

| 2. Rapid or accelerating motor dysfunction (including gait and balance) or non-motor disease progression (including severe dementia, dysphagia, bladder dysfunction, stridor (in MSA)) and disability (restricted to bed or chair-bound status, unintelligible speech, need for pureed diet or required significant assistance for ADLs), or | |

| 3. Has advanced dementia and meets hospice referral criteria based on Medicare’s Advanced Dementia Prognostic Tool criteria or the Minimum Data Set-Changes in Health, End-stage disease, and Symptoms and Signs Score criteria. | |

As part of the above, I recommend interviewing the primary caregivers to examine the last two weeks, the last month, the last three months, and the last six months to paint a picture of the frequency of moderate to significant declines. Based on the writer’s experiences, a patient with one or more moderate to major declines every four to eight weeks or less should be eligible.

The challenges of admitting patients with end-stage Parkinson’s disease to hospice care are complex, as evidenced by the experiences shared by hospice professionals. The existing guidelines for identifying end-stage Parkinson’s patients for hospice admission do not fully capture the nuances of the disease progression, leading to frequent discharges for failure to decline. The discussion among hospice nurses has shed light on various factors to consider, such as decline in function, weight loss, swallowing and speech difficulties, mobility challenges, and other clinical indicators.

Several potential solutions have been proposed to address these challenges. One approach is to utilize the Hospice Terminal Prognosis: Non-Disease Specific Decline in Clinical Status Guidelines, which outline various criteria for measuring irreversible decline in clinical status. Additionally, consideration of a peer-reviewed article on end-stage Parkinson’s disease and interviewing the primary caregiver to assess the frequency of moderate to significant declines over specific time frames have been suggested as potential solutions.

In conclusion, the identification of end-stage Parkinson’s patients for hospice admission requires a comprehensive and individualized approach that considers each patient’s unique progression of the disease. By incorporating the insights and experiences shared by hospice professionals and utilizing the proposed solutions, the accuracy of admitting Parkinson’s patients in the terminal stage to hospice care can be improved, ultimately ensuring appropriate and timely support for these individuals and their families.

Appropriate Clinical Factors to Consider During Recertification of Medicare Hospice Patients

Medicare Resources for Clinicians (Home Health & Hospice)

Excerpts from Medical Guidelines for Determining Prognosis in Selected NonCancer Diseases

Hospice Determining Terminal Status

End-Stage Parkinson’s Disease Hospice Eligibility

Holistic Nurse: Skills for Excellence book series

Empowering Excellence in Hospice: A Nurse’s Toolkit for Best Practices book series