Category: About Hospice

Articles about hospice dispelling myths and bring more light to end-of-life topics.

Articles about hospice dispelling myths and bring more light to end-of-life topics.

When it comes to hospice care, one common question that arises is whether terminally ill patients should continue seeing their regular doctor or specialists. As an experienced hospice nurse, I have witnessed the benefits and challenges of maintaining these relationships. In this article, we’ll explore the pros and cons of hospice patients still visiting their general practitioners and specialists from the perspective of patients and their families.

What does a typical day, a typical week look like for a visiting hospice registered nurse case manager look like?

As an experienced hospice nurse, I understand how overwhelming and emotional it can be for terminally ill patients and their loved ones to navigate the hospice process. Hospice care is a compassionate and comprehensive approach to end-of-life care, designed to provide comfort, pain management, and emotional support to patients and their families. However, many people have questions about hospice eligibility and hospice recertification. In this article, I will provide a generalized guide to help you understand these important aspects of hospice care.

I’ve seen firsthand how important it is to understand comfort and discomfort in hospice care. Let’s dive into these terms and how they relate to end-of-life care.

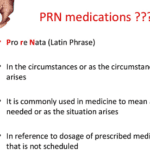

Hospice comfort medications play a vital role in managing end-of-life symptoms. From morphine for pain and breathing difficulties to lorazepam for anxiety and restlessness, these medications are carefully administered to enhance quality of life while ensuring patient comfort and dignity.

Hey there, my friend! As an experienced hospice nurse, I understand that managing symptoms for comfort is crucial for terminally ill patients. One of the ways we do this is through PRN medications. Today, I want to help you understand PRN medications and how they can be used in conjunction with scheduled medications.

Hospice care offers a specialized service known as the Continuous Care Benefit. This unique care type provides crucial 24-hour support to patients who are going through an acute symptom crisis. In this article, we'll delve into what Continuous Care Benefit is, who's eligible for it, how it operates, why it's important, how to access it, and its duration.

Understanding Hospice Care: A Guide for Families

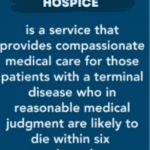

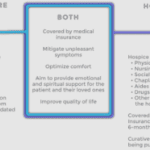

If you or your loved one is facing a serious illness and needs extra care and support, hospice care may be the right choice. Hospice is a special kind of care that helps people who are nearing the end of their lives feel as comfortable and peaceful as possible.

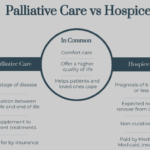

When a loved one is diagnosed with a terminal illness, hospice care can provide comfort and dignity in their final days. Hospice care is a type of palliative care that focuses on relieving pain and symptoms rather than curing the disease. It also offers emotional and spiritual support to the patient and their family.

However, choosing a hospice agency is not easy. Many factors must be considered, such as the quality of care, the agency's location, the level of services, and the patient’s rights. This article will discuss these factors and provide tips on choosing the best hospice agency for your loved one.

Hospice care focuses on providing comfort and quality of life for people with terminal illnesses and life expectancies of six months or less. While hospice care can be a difficult decision for families, it can also be a source of support and relief during a challenging time. In this article, we will explain the process of getting your loved one into hospice care and answer some common questions.

A review of the implications of each choice for the terminally ill patient as well as the loved ones of those who are terminally ill. This form comes into practice typically under two conditions… no pulse and is not breathing OR has a pulse and/or is breathing (but while not mentioned is typically in the last two weeks of life if no measures are taken with the understanding that any and all measures do not guarantee a longer time frame). Let’s review the form below:

This short article is meant for hospice patients, family members, and friends.

It’s common to read various social media posts where a patient, family member, or friend does the right thing by calling their hospice provider to alert them of a change of condition or otherwise significant issue for on-call to come out for an unscheduled visit. Also, common is follow up posts where the writer asked, “it’s been ______ (minutes, hours) since the call, I hope they show up.”

There are several things that go on behind the scenes when you or your loved one is admitted to a hospice provider. Some of them you may never see because it doesn’t impact the care provided and received. Others like the hospice benefit periods may only come out of the woodwork (so to write) at certain times and can either cause joy or distress depending on one’s point of view.

The goal of this article is to keep it simple and smile (my version of the K.I.S.S. principal) understanding of hospice benefit periods. When a person is first admitted to a hospice provider (having never been on hospice), they start off (behind the scenes) in benefit period number one. This is the first half (90-days/3-months) of the estimated six-months or less to live. Benefit period number two is the second half (3 more months/90-days). And since a terminal illness doesn’t come with guarantees that one will pass in six months or less, Medicare allows for (with fine print through the entire journey) an unlimited number of sixty-day (two months at a time) benefit periods.

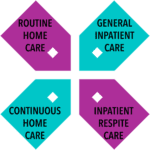

This article is meant to help families and new hospice staff understand the four hospice care levels. According to Medicare guidelines, several levels of care govern hospice services in the United States of America, whether the patient uses Medicare or not.

Hospice care is a vital service that provides compassionate and specialized support to individuals with life-limiting illnesses, particularly when they receive care at home. Understanding what home hospice covers is essential for patients and their families to ensure comprehensive and personalized end-of-life care. This article aims to shed light on the various aspects of home hospice care, including medications, durable medical equipment, staffing support, and expertise in managing the natural dying process. By delving into these details, individuals can make informed decisions and better comprehend the valuable assistance hospice care provides during this sensitive time.

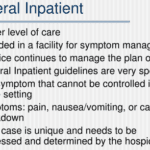

GIP, or General Inpatient Hospice, is an often misunderstood aspect of hospice care. Both hospital staff and families sometimes have misconceptions about GIP. Families may assume it's readily available upon request, while hospital professionals may believe it allows patients to remain in the hospital indefinitely, even when death is weeks away. This article will clarify the basics of GIP for hospice, including eligibility requirements, doctor's orders, care plans, documentation, and education. We'll conclude with two real-life cases to illustrate these points.

A hospice house is a peaceful, home-like residence where terminally ill people receive short-term hospice care. It is designed to provide a setting as close to home as possible, allowing for more freedom than a traditional facility. Hospice houses are typically run by not-for-profit organizations and are financed by donations, making them more economical for families who cannot afford skilled nursing facilities. Unlike inpatient hospice units (IPUs), hospice houses work with several hospice providers, allowing families to choose the provider that best suits their needs. They also follow a more flexible visitation policy, allowing families to visit 24x7 without appointments.

Hospice care is a specialized form of medical care for individuals with a life expectancy of six months or less, focusing on comfort, quality of life, and symptom management. It affirms life and recognizes dying as a natural process, neither hastening nor postponing death. The aim of hospice is to help patients live as fully and comfortably as possible, providing comprehensive support for both the patient and their family. This unique approach to care is exemplified by the stories of patients with terminal cancer who, with the help of hospice, were able to fulfill their final wishes, such as feeling the sun on their face or visiting the beach one last time. These experiences highlight that hospice is not just about dying, but about making the most of the time that remains, finding joy, and creating meaningful moments.

Navigating conversations about Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders with terminally ill patients and their families can be challenging yet crucial for ensuring that the patient's wishes and comfort are prioritized. The decision between opting for DNR or full code often involves delicate emotions, medical considerations, and ethical concerns. In this article, we will delve into a methodology that has proven effective in facilitating these discussions, particularly in the context of hospice care. Drawing from years of experience and successful outcomes, we'll explore approaches that prioritize compassion, clarity, and patient-centered care. Additionally, we'll reference valuable resources to enhance understanding and guide these critical conversations.

Autonomy, the right to receive or refuse medical treatment is a crucial element of health care ethics (American Nurses Association (ANA), 2011; Plakovic, 2016). Nurses are involved in helping patients and families be aware of when end-of-life is occurring, and in educating the patient and family about end-of-life legislation that helps guide everyone committed to continue the right of patient autonomy when the patient is no longer able to express their wishes. Before the Patient Self Determination Act, we had the famous cases of Karen Ann Quinlan and Nancy Cruzan who were, from a point-of-view, forced to suffer for ten or more years of futile treatment (Miller, 2017). Now, we have advanced directives that allow patients to express their wishes while they are able, yet we still have ethical dilemmas when either those needs are expressed vaguely or not at all. It is in the best interest of the patient and the patient's loved ones for advanced directives to be utilized and kept up to date.