Delirium vs Terminal Restlessness

Published on March 31, 2023

Updated on May 5, 2024

Published on March 31, 2023

Updated on May 5, 2024

Table of Contents

As an experienced hospice nurse, I understand how difficult it can be to distinguish between delirium and terminal restlessness. Both conditions can cause significant distress for the patient and their loved ones, and nurses must be able to tell the difference between them to provide the best possible care. In this article, I will share my knowledge and experience to help new hospice nurses understand the differences between delirium and terminal restlessness and how to rule out delirium.

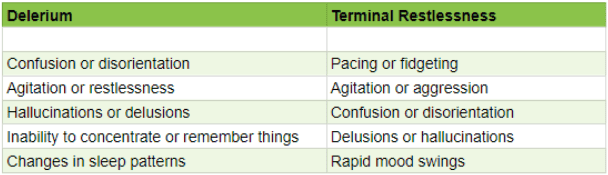

Delirium is a sudden change in mental status that can occur in patients who are seriously ill, especially those who are elderly or have underlying health conditions. It is characterized by a disturbance in attention and awareness and changes in thinking, perception, and behavior. Common symptoms of delirium include:

Various factors, including constipation, urine retention, medication side effects, infections, dehydration, and metabolic imbalances can cause delirium. It’s important for nurses to be aware of the risk factors for delirium and to monitor patients closely for any signs or symptoms.

Terminal restlessness is a type of delirium that can occur in patients who are in the final stages of a terminal illness. It is characterized by agitation, anxiety, and restlessness, as well as cognitive impairment and mood changes. Common symptoms of terminal restlessness include:

Terminal restlessness is irreversible and is a standard part of the natural dying process that can be managed to reduce distress to the patient and their loved ones.

While delirium and terminal restlessness share some common symptoms, there are a few key differences that can help nurses distinguish between the two:

As a hospice nurse, it’s essential to approach each patient individually and consider their unique medical history and symptoms when diagnosing. Suppose you suspect that a patient is experiencing delirium or terminal restlessness. In that case, it’s essential to consult with the interdisciplinary team and develop a plan of care that addresses the patient’s physical, emotional, and spiritual needs.

Consider the following reversible causes and evaluate if the patient is having any of these issues and then address them appropriately:

Pain: Does the patient have unmanaged pain? How is the patient’s pain currently being managed? What changes can take place to manage the patient’s pain better?

Constipation: When was the patient’s last bowel movement? If it has been more than three days or is unknown, treat for constipation unless contraindicated.

Urine retention: If the patient does not have end-stage renal disease and is anuric, are they urinating? Palpate the patient’s bladder and obtain an order for a bladder scan or straight CATH with education that a chronic Foley may need to be placed.

Infection: Assess for UTI, respiratory infection, GI infection, and sepsis. If the infection is found, work with the provider to be clear on communicating known allergies and following any pre-existing orders to treat or not treat infection (some states, like Pennsylvania, allow the POA/family to make that determination). Keep in mind sepsis may not be reversible if caught late.

Recently broken bones or fractures: assess for internal bleeding, remembering blood is a powerful laxative; assess for blood in the stool and any coffee ground emesis. Please keep in mind that if there is internal bleeding, like sepsis, which is caught too late, typical delirium may turn into terminal restlessness that leads to death.

Dehydration: If the patient is awake and alert with an intact gag reflex, are they hydrated enough? If not, encourage fluids.

Medications: Were there recent medication changes—new medications, changing doses, or discontinuing drugs? It may be possible that the medicines were stopped without proper titration. Consider reviewing all the medications the patient is taking with a hospice pharmacist to rule out medication-induced delirium.

Metabolic imbalances: Electrolyte imbalances and metabolic disorders, such as liver or kidney failure, can cause delirium. Treating the underlying condition can help alleviate symptoms. Remember that if the patient has had frequent loose stools or vomiting with emesis, they will have an electrolyte imbalance and dehydration.

Consider increasing your visit frequency while you rule out delirium; consider your resources, such as your fellow team members, medical director, hospice pharmacists, and the patient’s attending provider.

Include the family, as they know their loved one best and can help share critical information, such as whether the patient suffered delirium in the past and what helped or didn’t help. Ask them to paint a picture of what that looked like in the past.

Delirium and terminal restlessness are distressing to the patient, the caregivers, and the family. Be diligent in communicating your findings to the caregivers and family. Coordinate with the IDG team and everyone involved in the patient’s care to ensure everyone is on the same page.

Terminal restlessness typically occurs within the transitioning stage of the dying process and usually indicates there are only hours to days for the patient to live (keep in mind days can become a week or two). Delirium can occur anywhere within the patient’s journey towards the end of life and can sometimes be confused with terminal restlessness. Hospice staff needs to work towards ruling out delirium — which is treatable — to provide the best of care with comfort in mind.

Reversible delirium in terminally ill patients

A Change in Behavior: Delirium, Terminal Restlessness, or Dementia, A Pragmatic Clinical Guide

Delirium in Older Persons: Evaluation and Management

Delirium (booklet / PDF)

The Importance of Caregiver Journaling

Reporting Changes in Condition to Hospice

CaringInfo – Caregiver support and much more!

Surviving Caregiving with Dignity, Love, and Kindness

Caregivers.com | Simplifying the Search for In-Home Care

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. The amount generated from these “qualifying purchases” helps to maintain this site.

Take Back Your Life: A Caregiver’s Guide to Finding Freedom in the Midst of Overwhelm

The Conscious Caregiver: A Mindful Approach to Caring for Your Loved One Without Losing Yourself

Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved

Final Gifts: Understanding the Special Awareness, Needs, and Communications of the Dying

Providing Comfort During the Last Days of Life with Barbara Karnes RN (YouTube Video)

Preparing the patient, family, and caregivers for a “Good Death.”

Velocity of Changes in Condition as an Indicator of Approaching Death (often helpful to answer how soon? or when?)

The Dying Process and the End of Life

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. The amount generated from these “qualifying purchases” helps to maintain this site.

Gone from My Sight: The Dying Experience

The Eleventh Hour: A Caring Guideline for the Hours to Minutes Before Death